The abdominal peritoneum is a thin, serous membrane that lines the abdominal cavity and covers the internal organs. It plays a crucial role in protecting abdominal organs, facilitating movement, and reducing friction. Like other body structures, the peritoneum has a nerve supply that helps in sensation, reflex responses, and autonomic regulation.

Understanding the nerve supply of the peritoneum is essential for diagnosing abdominal pain, surgical procedures, and medical conditions affecting the abdomen. This topic provides a detailed overview of the nervous control of the peritoneum, including the somatic and autonomic nerve innervation.

Overview of the Abdominal Peritoneum

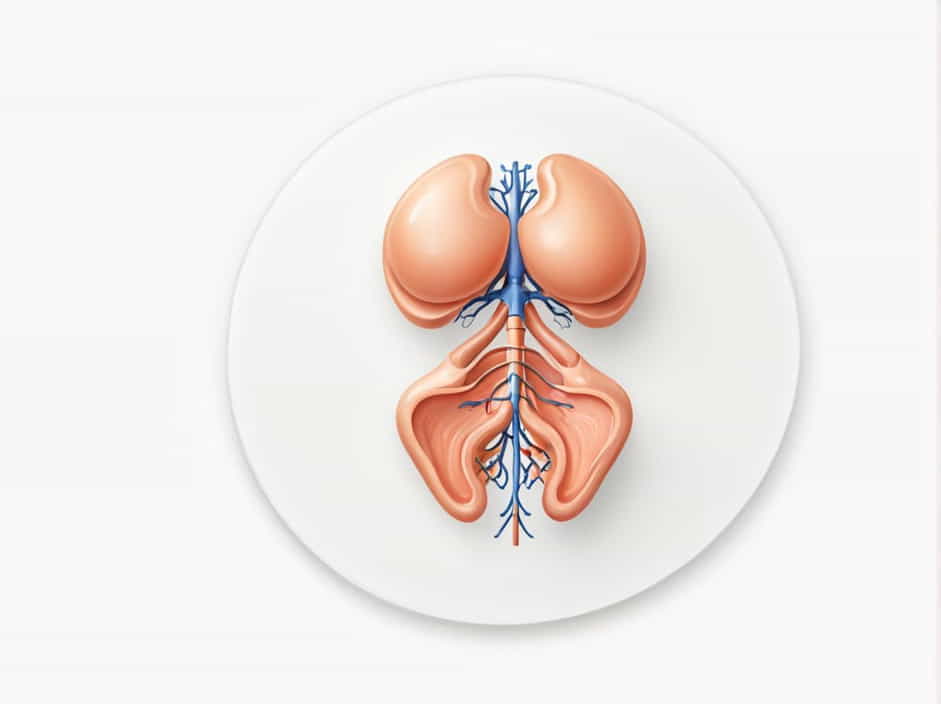

The peritoneum is divided into two layers:

- Parietal peritoneum – Lines the inner surface of the abdominal wall.

- Visceral peritoneum – Covers the abdominal organs.

These two layers have different nerve supplies, which affect their sensitivity to pain and other stimuli.

Nerve Supply of the Parietal Peritoneum

The parietal peritoneum is highly sensitive to pain, pressure, temperature, and touch. It has a somatic nerve supply, which means it is innervated by nerves from the spinal cord and can generate localized pain sensations.

1. Phrenic Nerve (C3, C4, C5)

The phrenic nerve supplies the central diaphragm and its overlying peritoneum.

- Pain from the central diaphragm refers to the shoulder (C3-C5 dermatomes).

- This explains why patients with diaphragmatic irritation (e.g., peritonitis, subphrenic abscess) may experience shoulder pain.

2. Intercostal Nerves (T7-T11) and Subcostal Nerve (T12)

These nerves supply the anterolateral abdominal wall and its overlying peritoneum.

- Pain from the anterior abdominal peritoneum is felt in the same area as the affected region.

- It is sharp and localized, similar to pain from the skin.

3. Iliohypogastric and Ilioinguinal Nerves (L1)

These nerves provide innervation to the lower abdominal wall and peritoneum near the inguinal region.

- Pain in this area is localized to the lower abdomen and groin.

- Commonly involved in inguinal hernias and lower abdominal surgeries.

Nerve Supply of the Visceral Peritoneum

The visceral peritoneum is not highly sensitive to pain, temperature, or touch because it is supplied by autonomic nerves. Instead, it responds to stretching, chemical irritation, and distension.

1. Sympathetic Nerve Fibers (Thoracic and Lumbar Splanchnic Nerves)

The sympathetic nervous system primarily regulates vasoconstriction and pain sensation in the visceral peritoneum.

- Sympathetic fibers arise from the thoracic (T5-T12) and lumbar (L1-L2) spinal levels.

- Pain from the visceral peritoneum is poorly localized and is often referred to midline structures.

For example:

- Foregut organs (stomach, liver, pancreas) → Pain referred to epigastric region (T5-T9).

- Midgut organs (small intestine, appendix) → Pain referred to umbilical region (T10-T11).

- Hindgut organs (colon, rectum) → Pain referred to suprapubic region (T12-L2).

2. Parasympathetic Nerve Fibers (Vagus Nerve and Pelvic Splanchnic Nerves)

The parasympathetic nervous system helps in digestive function and visceral sensation.

- Vagus nerve (Cranial Nerve X) – Supplies parasympathetic innervation to foregut and midgut organs.

- Pelvic splanchnic nerves (S2-S4) – Supply hindgut structures (distal colon and rectum).

Pain from visceral peritoneal irritation is often diffuse, dull, and referred to distant regions rather than localized pain.

Clinical Significance of Peritoneal Nerve Supply

1. Peritonitis and Referred Pain

- Inflammation of the peritoneum (peritonitis) causes severe abdominal pain.

- Parietal peritoneal irritation produces sharp, localized pain.

- Visceral peritoneal irritation results in dull, poorly localized pain.

For example, in appendicitis:

- Early pain is visceral (mid-abdomen, umbilical region) due to irritation of the midgut peritoneum.

- Later pain becomes localized to the right lower quadrant when the parietal peritoneum is affected.

2. Referred Pain from Diaphragmatic Peritoneum

- Gallbladder inflammation (cholecystitis) can irritate the diaphragm, causing shoulder pain (C3-C5, phrenic nerve distribution).

- This occurs due to shared nerve pathways between the diaphragm and shoulder region.

3. Hernias and Nerve Compression

- In inguinal or femoral hernias, the ilioinguinal and iliohypogastric nerves may be compressed.

- This leads to pain radiating to the groin and lower abdomen.

4. Autonomic Dysfunction in Abdominal Disorders

- Conditions like irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and gastroparesis involve abnormal autonomic nerve function.

- Patients may experience abdominal discomfort, bloating, and altered bowel movements due to disrupted autonomic signaling.

Surgical Considerations for the Peritoneal Nerve Supply

1. Anesthesia and Pain Management

- Local anesthesia is effective for the parietal peritoneum but not the visceral peritoneum due to their different nerve supplies.

- Laparoscopic surgeries cause visceral peritoneal stretch, leading to postoperative shoulder pain (phrenic nerve irritation).

2. Nerve Injury During Abdominal Surgery

- Intercostal nerve damage may lead to chronic abdominal pain.

- Sympathetic nerve disruption can affect gut motility and function.

The nerve supply of the abdominal peritoneum is essential for pain perception, organ function, and reflexive responses. The parietal peritoneum receives somatic innervation, leading to sharp, localized pain, while the visceral peritoneum is supplied by autonomic nerves, resulting in diffuse, poorly localized pain.

Understanding this complex nerve network is crucial for diagnosing abdominal pain, managing surgical interventions, and treating peritoneal disorders.